So why Al Simmons?

Why is it that Al Simmons – of the few hundred men who are in baseball’s Hall of Fame (not to mention the thousands who have played major league baseball) – somehow became my historical favorite?

I’m not at all sure. What is it that elevates in our hearts and heads one man’s story over another’s? It’s almost impossible to grasp those workings. All we can do is to acknowledge that some stories grab some of us and other stories take hold of others.

And all I know is that from the time I began to read about Al Simmons and his life, as a ballplayer and as a person, his tale resonated inside me. And I became a fan.

A fan? Of a ballplayer now dead for fifty years? Well, yes. I would guess I’m not all that different from the other people – men, mostly, I assume – who inhabit the world of simulation baseball games, in which we routinely have men long dead perform marvelous and perplexing deeds on our table tops or on our hard drives. We all have our favorites, depending, I suppose on personal views, strategic inclinations (pitching vs. hitting; smallball vs. power, and so on) and other aspects of our personalities and lives.

It was, in fact, a simulation baseball game that brought Al Simmons to my attention, a game called Sports Illustrated Superstar Baseball, which I bought in 1985. It was about that time – I was 31 – that I began to not only play the game but to dig into the history of baseball, something I’d not done to any great degree up to then.

Oh, I’d played other simulation baseball games before, most notably Strat-O-Matic, which a long-time friend of mine had. During a visit to his home in early 1985, he and I had played for several hours with historic teams, an evening that might have sparked my interest in buying my own simulation game. Soon after that, I spotted Superstar Baseball on the shelf of a local hobby shop. And the next thing I knew, I was gently separating perforated player cards and planning the creation of my six-team simulated league.

I knew at least something about many of the players whose cards were in the game, of course: I was familiar with the names and to some extent the performance value of the truly great players, Ruth, Gehrig, Wagner, Johnson, Cobb and so on. And I knew about the players who had been on the field when I was a kid: Killebrew, Koufax, Gibson, Mays and the others.

But there were a fair number of cards for players who were only vaguely familiar or were utter mysteries to me. I’d not done much reading of baseball history at that point. And I found myself reading the biographies on the backs of the cards in my effort to understand why this player and that had been included in the game: Who was Stan Coveleski? Who was Billy Cox? Harry Heilmann? Edd Roush? Kid Nichols? And who was Al Simmons?

Al didn’t play much during my first season. Shortly after I dealt the cards out to my six teams and started my season, I realized that my Portland team had too many outfielders and not enough pitchers; Nashville had extra pitchers. So in the first trade I engineered, I sent Al Simmons from Portland to Nashville for Stan Coveleski. Simmons batted about .250 in limited duty for Nashville, which finished sixth; Coveleski was 12-11 for Portland, which tied for fourth place. (For whatever it may be worth, in the twenty-three seasons I’ve played with Superstar Baseball, Al Simmons has been one of the ten best hitters, a performance perhaps a little better than one would expect.)

At the same time as I played that first season, I began to read about the history of the game and its players. I soon learned that I didn’t know much about baseball history at all – there were entire eras of the game that were blank to me until I began my reading, spurred on by one question: Who were the flesh and blood men who’d left behind careers that were reflected by the numbers and letters on the cards of my game?

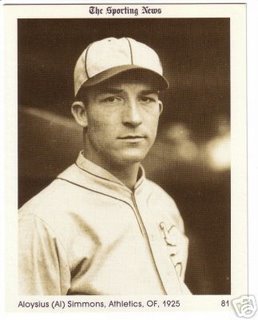

And as I dug into the history of those men, the story that for some reason resonated inside me the most was the story of Aloys Szymanski, a Milwaukee native who played 20 seasons as Al Simmons. I’ve heard two versions of the story behind the change in names; one says that a Milwaukee reporter grew tired of trying to spell “Szymanski” in accounts of Al’s early games and changed the name on his own; another says that Al saw the name “Simmons” in an advertisement for a store and adopted the name himself. Either way, by the time he came to the attention of Connie Mack and the Philadelphia Athletics, he was Al Simmons.

He had a hell of a career. In his Historical Baseball Abstract, Bill James ranks Al Simmons 71st among all the men who ever played major league baseball, putting him somewhere in the top 5 percent of players all-time. And yet, to the casual fan – a category in which I would put myself prior to 1985 – he’s almost unknown. The Athletics during his prime years were a good team, and for three seasons – 1929 through 1931 – were one of the greatest teams of all time. But as good as Al Simmons was during those seasons, he was likely only the fourth best player on his own team.

Great teams, of course, have great players. The Athletics had four: pitcher Lefty Grove, first baseman Jimmie Foxx, catcher Mickey Cochrane, and Simmons. One could argue without looking silly that Grove, Foxx and Cochrane might have been the best ever at their positions. I don’t think any of them were, but a reasonable case could be made for all three. Al Simmons, as great as he was, could not be reasonably argued to be among the three greatest outfielders of all time.

I’ve gotten a feeling over the years, as I’ve read, that Al Simmons was an intense, nearly angry, man and player. I sense that he burned, if you will, with a very bright flame and sense as well – this may be pure supposition, but it’s a feeling I get from reading about him and his life – that he never quite accomplished as much as he would have liked to. If that’s the case, I wonder how much of that feeling might have come from being a great baseball player and still being only the fourth-best player on his main team?

After nine seasons in Philadelphia, Simmons was sold to the Chicago White Sox, for whom he had two very good seasons and one mediocre one. After that, he became, in Bill James’ words, “a baseball nomad,” playing with less and less value in several cities until retiring after the 1944 season.

He wanted to manage, James notes, but reading between the lines, one senses that his temperament was not suited for that role. Still, Simmons was something close to a de facto manager during the late 1940s as a coach for the Athletics when owner/manager Mack was in his declining years. He coached in Cleveland in 1950 and retired, going home to Milwaukee, where, according to James, he began to drink heavily. He died of a heart attack at the age of 54 in 1956.

Those are the bare bones of a life. And there is something about that life – maybe something that I sense should be in that story, something seemingly hidden – that fascinates me.

What is it? I have no idea. Perhaps it’s the thought that someone can be very good, even great at what he does, and still be to a large extent left behind by time. And it seems to me that’s what happened to Al Simmons. Was he a household name during his prime in the 1920s and early 1930s? I don’t know. He likely was, at least among households that cared about major league baseball. He’s not now.

On the day in 1985 that I opened my game and began to separate the cards, I was not a baseball historian – I would guess I am one now, at least on an amateur level – but I was fairly aware of sports history. And I didn’t know who Al Simmons was.

For all of my reading and thinking, and all the bits of information I have in my head and in my library, I’m still not sure I know who Al Simmons was. And I don’t really have an answer as to why his story fascinates me more than the stories of other players whose lives I’ve studied.

As I stood at Al’s grave in Milwaukee in May, holding a baseball I bought the day before during a Brewers’ game at Miller Park, I was struck with a thought: Simmons retired to Milwaukee after the 1950 season. In 1953, the Braves came to town from Boston, and they were there for three-and-a-half seasons before Al died.

How often, I wondered as I stood at his grave, did Aloys Szymanski sit in old County Stadium and watch the Braves play ball? How often did anyone recognize him and know he’d been one of the best ballplayers ever? How often did he watch Eddie Mathews or Henry Aaron slash a double into the gap and think, “I used to do that,” as the outfielders pursued the ball?

Millions are born. Millions are forgotten. So why should it matter to me that one son of Polish immigrants, one young man from Milwaukee, played baseball and played it well and then faded from public memory? I don’t know. But for some reason, it does.

So I wrote on the baseball, telling a man who died before I was three years old that he was not forgotten. And I left it at the grave.